dimanche, 05 juin 2022

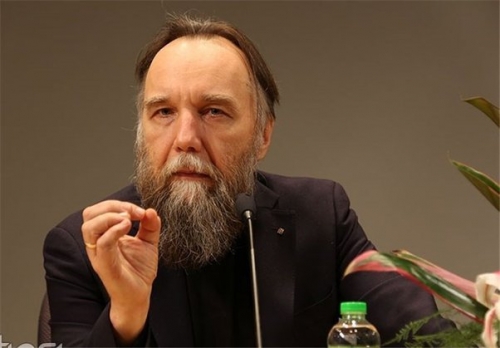

Alexandre Douguine: la philosophie gagnante

La philosophie gagnante

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitika.ru/en/article/winning-philosophy?fbclid=IwAR0XdgpI5Ub792MgePrqc09IXFY3Ryt4BTMcLvSOX0EdASDw-j3DGR-bXjo

Des réformes internes significatives devraient logiquement commencer en Russie. C'est ce qu'exige l'OMS, qui, à l'extrême, a aggravé les contradictions avec l'Occident - avec toute la civilisation occidentale moderne. Aujourd'hui, tout le monde peut voir qu'il n'est plus sûr d'utiliser simplement les normes, les méthodes, les concepts, les produits de cette civilisation. L'Occident répand son idéologie en même temps que ses technologies, imprégnant toutes les sphères de la vie. Si nous nous reconnaissons comme faisant partie de la civilisation occidentale, nous devrions accepter volontairement cette colonisation totale et même en profiter (comme dans les années 1990), mais dans le cas de la confrontation actuelle - qui est fatale ! - cette attitude est inacceptable. De nombreux occidentaux et libéraux en ont pris pleinement conscience et ont quitté la Russie au moment même où la rupture avec la civilisation occidentale était devenue irréversible; et la situation est bel et bien devenue irréversible le 24 février 2022, et même deux jours plus tôt - au moment de la reconnaissance de l'indépendance de la RPD et de la RPL - le 22 février 2022.

En principe, chacun a le droit de faire un choix de civilisation entre la loyauté et la trahison. Le libéralisme est en train de perdre en Russie et les libéraux sont cohérents lorsqu'ils partent. C'est plus compliqué avec ceux qui sont encore là. Je fais référence aux Occidentaux et aux libéraux qui partagent encore les normes de base de la civilisation occidentale moderne, mais qui, pour une raison quelconque, continuent à rester en Russie malgré le fossé qui s'est déjà formé entre la Russie et l'Occident; ils constituent le principal obstacle à des réformes patriotiques authentiques et significatives.

Les réformes sont inévitables car la Russie se retrouve non seulement coupée de l'Occident, mais essentiellement en guerre avec lui. À la veille de la Grande Guerre patriotique, l'URSS disposait d'un nombre suffisant d'importantes entreprises stratégiques créées par l'Allemagne nazie, et les relations entre l'URSS et le Troisième Reich n'étaient pas particulièrement hostiles ; mais après le 22 juin 1945, la situation a évidemment changé radicalement. Dans ces circonstances, la poursuite de la coopération avec les Allemands - légitime et encouragée avant la guerre - a pris une toute autre signification. Il s'est passé exactement la même chose après le 22 février 2022: ceux qui ont continué à rester dans le paradigme de la civilisation hostile - libérale-fasciste - avec laquelle nous étions en guerre, se sont retrouvés en dehors de l'espace idéologique qui avait clairement émergé avec le début de la Seconde Guerre mondiale.

Entre-temps, la présence de l'Allemagne à la veille de la Seconde Guerre mondiale a été identifiée en URSS, tandis que la présence de l'Occident libéral-fasciste russophobe à la veille de l'OMS était presque totale. Les technologies méthodologiques, les normes, le savoir-faire et, dans une certaine mesure, les valeurs occidentales imprègnent toute notre société. C'est ce qui nécessite une refonte radicale. Mais qui y parviendra ? Les personnes qui ont été formées pendant la perestroïka ? Les libéraux et les criminels des années 1990 ? Les personnes des années 1980 et 1990 qui ont été formées et éduquées dans les années 2000 ? Toutes ces périodes ont été fondamentalement influencées par le libéralisme en tant qu'idéologie, en tant que paradigme, en tant que position fondamentale et globale dans la philosophie, la science, la politique, l'éducation, la culture, la technologie, l'économie, les médias, et même la mode et la vie quotidienne. La Russie contemporaine ne connaît que les vestiges inertes du paradigme soviétique et tout le reste est pur occidentalisme libéral.

Il n'existe tout simplement pas de paradigme alternatif, du moins aucun au pouvoir ou parmi les élites, au niveau où devrait se dérouler la confrontation actuelle des civilisations.

Aujourd'hui, nous opposons l'Occident en tant que civilisation contre "la" civilisation, et nous devons préciser quel type de civilisation nous sommes, sinon aucun succès militaire, politique et économique ne nous aidera et tout sera réversible, la tendance changera et tout s'effondrera. Je ne parle même pas de la nécessité d'expliquer aux Ukrainiens qu'à partir de maintenant ils seront dans notre zone d'influence ou directement en Russie, qui sommes-nous après tout ? Pour le moment, il n'y a que l'inertie de la mémoire soviétique ("la grand-mère avec le drapeau"), la propagande nazie occidentale ("vatniki", "occupants"), nos succès militaires - pour l'instant seulement initiaux - et... la confusion totale de la population locale. Ici, la voix de la civilisation russe doit être entendue. Clairement, distinctement, de manière convaincante, et ses bruits devraient être entendus en Ukraine, en Eurasie et dans le monde entier. Ce n'est pas seulement souhaitable, c'est vital, tout comme les munitions, les missiles, les hélicoptères et les gilets pare-balles sont nécessaires au front.

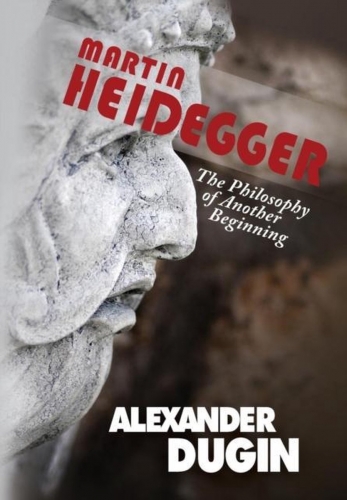

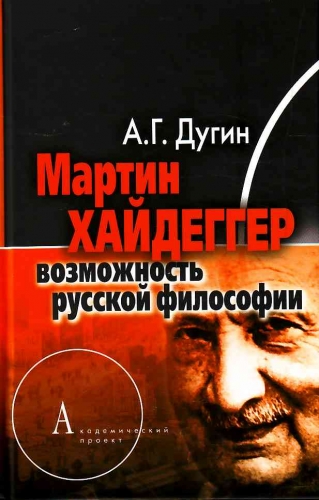

L'endroit le plus logique pour commencer les réformes est la philosophie. Il est nécessaire de former du personnel au Logos russe, soit sur la base d'une institution existante (après tout, aujourd'hui, aucune institution humanitaire ne fait, ne peut ou ne veut le faire - le libéralisme et l'occidentalisme dominent encore partout), soit sous la forme de quelque chose de fondamentalement nouveau. Hegel disait que la grandeur d'une nation commence par la création d'une grande philosophie. Il l'a dit et il l'a aussi fait. C'est exactement ce dont les philosophes russes ont besoin aujourd'hui, et non d'un vague accord à l'emporte-pièce avec l'Opération Militaire Spéciale. Nous avons besoin d'une nouvelle philosophie russe. Russe dans son contenu, dans son essence.

Par conséquent, la réforme de toutes les autres branches des sciences humaines et des sciences naturelles devrait partir de ce paradigme. La sociologie, la psychologie, l'anthropologie, la culturologie, ainsi que l'économie, et même la physique, la chimie, la biologie, etc. sont basées sur la philosophie, en sont des dérivés. Les scientifiques l'oublient souvent, mais écoutez comment sonne le synonyme occidental de PhD : n'importe laquelle des sciences humaines et naturelles ! - Ph.D. - Docteur en philosophie. Si vous n'êtes pas philosophe, vous êtes au mieux un apprenti, pas un scientifique (docteur est le mot latin pour "érudit", "savant").

C'est ici que se déroulera la bataille interne la plus importante pour l'initiation de réformes civilisatrices en Russie même (ainsi que dans tout l'espace de notre expansion, toute la zone de notre influence): la bataille pour la philosophie russe.

Il y a ici un pôle clairement modélisé de l'ennemi interne. Il s'agit des représentants du paradigme libéral, de la philosophie analytique au post-modernisme en passant par les cognitivistes et les transhumanistes, qui insistent de façon maniaque pour réduire l'homme à une machine. Je ne parle même pas des libéraux et des progressistes, des partisans du concept totalitaire de "société ouverte", du féminisme, des études et de la culture queer, élevés à la bourse des fraternités. Il s'agit d'une pure "cinquième colonne", quelque chose qui ressemble au bataillon Azov interdit en Russie.

Le portrait de l'ennemi philosophique de l'Idée russe, de la civilisation russe, est très facile à tracer. Il ne s'agit pas simplement de liens avec les centres scientifiques et de renseignement occidentaux (qui sont souvent des concepts assez proches), mais aussi de l'adhésion à un certain nombre d'attitudes plutôt formalisables :

- la croyance en l'universalité de la civilisation occidentale moderne (eurocentrisme, racisme civilisationnel),

- l'hyper-matérialisme, en passant par l'écologie profonde et l'ontologie orientée objet,

- l'individualisme méthodologique et éthique - d'où la philosophie du genre (comme option sociale) et, à la limite, le transhumanisme,

- le techno-progressisme, le développement de l'intelligence artificielle et des réseaux neuronaux "pensants",

- la haine des théologies classiques, de la Tradition spirituelle, de la philosophie de l'éternité,

- le déni de l'identité ou son dénigrement par ironie, en la ridiculisant,

- l'anti-essentialisme, etc...

Il s'agit d'une sorte d'"Ukraine philosophique", disséminée dans presque toutes les institutions scientifiques et universitaires qui ont un rapport quelconque avec la philosophie ou les épistèmes scientifiques de base. Ce sont des signes de russophobie philosophique, puisque l'Idée russe est construite sur la base de principes directement opposés.

- L'identité de la civilisation russe (slavophiles, danilovistes, eurasiens),

- le fait de placer l'esprit avant la matière,

- la communauté, la collégialité - une anthropologie collectiviste,

- un humanisme profond,

- la dévotion à la tradition,

- la préservation minutieuse de l'identité, de la nationalité,

- la croyance en la nature spirituelle de l'essence des choses, etc.

Ceux qui donnent le ton à la philosophie russe contemporaine défendent avec véhémence les attitudes libérales et rejettent avec la même véhémence les attitudes russes. C'est un puissant bastion du nazisme libéral en Russie.

C'est ce point du champ de tir de l'ennemi, cette hauteur, qu'il faut conquérir dans la phase suivante, et les nazis libéraux se défendent contre la philosophie avec la même férocité qu'Azov ou les terroristes ukrainiens désespérés de Popasna. Ils mènent des guerres d'information, écrivent des dénonciations sur les patriotes et utilisent tous les leviers de la corruption et de l'influence des appareils.

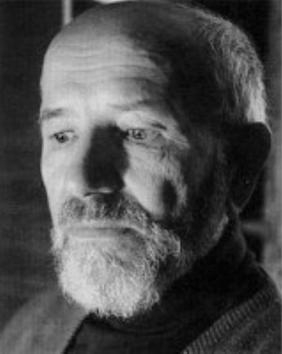

Il convient maintenant de rappeler une petite histoire - personnelle, mais très révélatrice - concernant mon renvoi de la MSU à l'été 2014 (notez la date) [Ed. Dugin en 2014 a été démis de sa chaire à l'Université d'État de Moscou au moment où le "printemps russe" dans le Donbass a échoué]. De 2008 à 2014, au département de sociologie de l'université d'État de Moscou, avec le recteur et fondateur du département, Vladimir Ivanovitch Dobrenkov (photo), nous avons organisé un centre actif d'études conservatrices, où nous nous occupions précisément de cela : le développement d'un paradigme épistémologique de la civilisation russe.

Nous n'avions pas hésité à soutenir le Printemps russe. En réponse, cependant, nous avons reçu une pétition cinglante de... philosophes ukrainiens (promue par le nazi de Kiev Sergey Datsyuk) appelant à "l'expulsion de Dobrenkov et de moi-même de l'Université d'État de Moscou" ; le plus étrange - mais à l'époque ce n'était pas très étrange - est que la direction de la MSU a fait exactement cela. Dobrenkov a été démis de ses fonctions de recteur et moi, franchement, je suis parti de mon propre chef, même si cela ressemblait à un licenciement. On m'a également proposé de rester, mais à des conditions humiliantes. Bien sûr, ce n'est pas Sadovnichy, qui s'était auparavant montré très courtois et ouvert, qui a approuvé ma nomination à la tête du département et a suivi toutes les procédures de vote du conseil académique de la MSU. Mais quelque chose s'est ensuite produit : le Printemps russe a été mis en veilleuse et la question du monde russe, de la civilisation russe et du Logos russe a été complètement retirée de l'ordre du jour ; toutefois, ceci est symbolique : les promoteurs de la suppression du Centre d'études conservatrices de l'Université d'État de Moscou étaient des nationalistes ukrainiens, des théoriciens et des praticiens du génocide russe dans le Donbass et dans l'ensemble de l'Ukraine orientale, exactement ceux avec qui nous sommes en guerre actuellement.

C'est ainsi que le nationalisme libéral a pénétré à l'intérieur de la Russie. Ou plutôt, il y a pénétré il y a longtemps, mais c'est ainsi que ses mécanismes fonctionnent. Une plainte vient de Kiev, quelqu'un au sein de l'administration la soutient, et une autre initiative visant à déployer l'Idée russe s'effondre. Bien sûr, vous ne pouvez pas m'arrêter: au fil des ans, j'ai écrit 24 volumes de ma "Noomachia", et les trois derniers sont consacrés au Logos russe, mais l'institutionnalisation de l'Idée russe a encore été retardée. Mon exemple, bien sûr, n'est pas un cas isolé. Quelque chose de similaire a été vécu par tous ou presque les penseurs et théoriciens engagés dans la justification de l'identité de la civilisation russe. Il s'agit d'une guerre philosophique, d'une opposition féroce et bien organisée à l'Idée russe, supervisée depuis l'étranger, mais menée par des libéraux locaux ou de simples fonctionnaires, qui suivent passivement les modes, les tendances et une stratégie d'information bien organisée d'agents d'influence directs.

Nous en sommes maintenant au point où l'institutionnalisation du discours russe est nécessaire. Tout le monde a vu dans notre guerre de l'information à quel point les humeurs et les processus de la société sont contrôlables et manipulables. Les affrontements les plus graves se produisent au niveau des paradigmes et des épistèmes. Celui qui contrôle le savoir, écrivait Michel Foucault, détient le vrai pouvoir. Le vrai pouvoir est le pouvoir sur l'esprit et l'âme des gens.

La philosophie est la ligne de front la plus importante, dont les conséquences sont bien plus importantes que les nouvelles d'Ukraine, que chaque Russe recherche si avidement en se demandant comment vont les soldats, quelles nouvelles lignes ont été saisies, ou si l'ennemi a faibli. C'est là que réside le principal obstacle à notre victoire.

Nous avons besoin d'une philosophie de la victoire. Sans elle, tout sera vain et tous nos succès se transformeront facilement en défaites.

Toutes les véritables réformes doivent commencer dans le royaume de l'Esprit. Et puisqu'il faut chercher des nouvelles du front dans les actualités - eh bien, qu'en est-il de l'Institut de philosophie ? Toujours debout ? A-t-il déjà capitulé ?

12:15 Publié dans Actualité, Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, actualité, russie, alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, logos russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 01 juin 2022

De l'Etat-Civilisation

De l'Etat-Civilisation

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitika.ru/article/gosudarstvo-civilizaciya

L'OSU est unanimement reconnue par les experts compétents en relations internationales comme étant l'accord final et décisif qui amènera la transition d'un monde unipolaire à un monde multipolaire.

La multipolarité semble parfois intuitivement et claire, mais dès que nous essayons de donner des définitions précises ou une description théorique correcte, les choses deviennent moins claires. Je pense que mon ouvrage "Théorie d'un monde multipolaire" est plus pertinent que jamais. Mais comme les gens ne peuvent plus lire, surtout les longs textes théoriques, je vais essayer de partager ici les points principaux.

L'acteur principal dans un ordre mondial multipolaire n'est pas l'État-nation (comme dans la théorie du réalisme en relations internationales) mais pas non plus un gouvernement mondial unifié (comme dans la théorie du libéralisme en relations internationales). C'est l'État-civilisation. D'autres noms lui sont donnés : le "grand espace", l'"Empire", l'"œcumène".

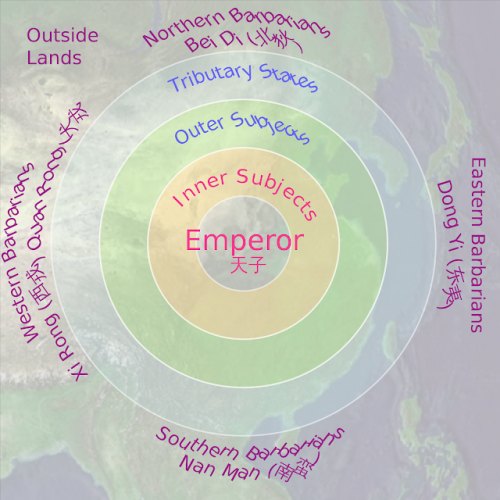

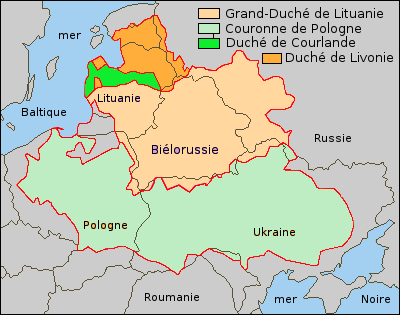

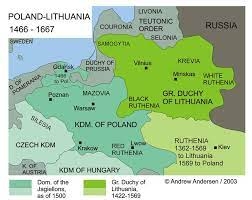

Le terme "État-civilisation" est le plus souvent appliqué à la Chine. À la fois à la Chine ancienne et moderne. Dès l'Antiquité, les Chinois ont développé la théorie du "Tianxia" (天下), "Empire céleste", selon laquelle la Chine est le centre du monde, étant le point de rencontre du Ciel unificateur et de la Terre diviseuse. L'"Empire céleste" peut être un État unique, ou être démantelé en ses composants, puis réassemblé. En outre, la Chine Han proprement dite peut également servir d'élément culturel constitutif pour les nations voisines qui ne font pas directement partie de la Chine - avant tout, pour la Corée, le Vietnam, les pays d'Indochine et même le Japon, qui a acquis son indépendance.

L'État-nation est un produit du Nouvel Âge européen, et dans certains cas une construction post-coloniale. L'État-Civilisation a des racines anciennes et... des frontières mouvantes, incertaines. L'État-civilisation est tantôt poussé en avant, tantôt élargi, tantôt contracté, mais reste toujours un phénomène permanent. (C'est, avant tout, ce que nous devons savoir sur notre SSO).

La Chine moderne se comporte strictement selon le principe du "Tianxia" en politique internationale. L'initiative "One Belt, One Road" est un exemple brillant de ce à quoi cela ressemble dans la pratique. L'Internet de la Chine, qui ferme tous les réseaux et ressources susceptibles d'affaiblir son identité civilisationnelle, montre comment les mécanismes de défense sont mis en place.

L'Etat-civilisation peut interagir avec le monde extérieur, mais elle n'en devient jamais dépendante et conserve toujours son autosuffisance, son autonomie et son autarcie.

L'État-civilisation est toujours plus qu'un simple État, tant sur le plan spatial que temporel (historique).

La Russie gravite de plus en plus vers le même statut. Après le début du "Nouvel ordre mondial", ce n'est plus un simple vœu pieux, mais une nécessité urgente. Comme dans le cas de la Chine, la Russie a toutes les raisons de prétendre être précisément une civilisation. Cette théorie a été développée de manière plus complète par les Eurasiens russes, qui ont introduit la notion d'un "État-monde" ou - ce qui est la même chose - d'un "monde russe". En fait, le concept de Russie-Eurasie est une indication directe du statut civilisationnel de la Russie. La Russie est plus qu'un État-nation (ce qu'est la Fédération de Russie). La Russie est un monde à part.

La Russie était une civilisation à l'époque de l'Empire, et elle est restée la même pendant la période soviétique. Les idéologies et les régimes ont changé, mais l'identité est restée la même.

Le combat pour l'Ukraine n'est rien d'autre qu'un combat pour l'État-civilisation. Il en va de même pour l'État d'union pacifique de la Russie et du Belarus et l'intégration économique de l'espace eurasien post-soviétique.

Un monde multipolaire est composé d'États et de civilisations. C'est une sorte de monde des mondes, un mégacosmos qui inclut des galaxies entières. Et ici, il est important de déterminer combien de ces États-Civilisations peuvent exister, même théoriquement.

Sans aucun doute, l'Inde appartient à ce type, c'est un État-civilisation typique, qui possède aujourd'hui encore suffisamment de potentiel pour devenir un acteur à part entière de la politique internationale.

Ensuite, il y a le monde islamique, de l'Indonésie au Maroc. Ici, la fragmentation en États et en différentes enclaves ethnoculturelles ne nous permet pas encore de parler d'unité politique. Il existe une civilisation islamique, mais son amalgame dans une civilisation d'État s'avère plutôt problématique. En outre, l'histoire de l'Islam connaît plusieurs types d'états-civilisations - des califats (le Premier, puis celui des Omeyyades, des Abbassides, etc.) aux trois parties de l'Empire de Gengis Khan converties à l'Islam (la Horde d'or, l'Ilkhan et le Chagatai ulus), la puissance perse des Safavides, l'État moghol et, enfin, l'Empire ottoman. Les frontières autrefois tracées sont à bien des égards toujours d'actualité. Toutefois, le processus consistant à les rassembler en une seule structure nécessite un temps et des efforts considérables.

L'Amérique latine et l'Afrique, deux macro-civilisations qui restent plutôt divisées, sont dans une position similaire. Mais un monde multipolaire impulsera d'une manière ou d'une autre les processus d'intégration dans toutes ces zones.

Maintenant, la chose la plus importante: que faire de l'Ouest ? La théorie du monde multipolaire dans la nomenclature des théories des relations internationales est absente de l'Occident moderne.

Le paradigme dominant y est aujourd'hui le libéralisme, qui nie toute souveraineté et toute autonomie, abolit les civilisations et les religions, les ethnies et les cultures, les remplaçant par une idéologie libérale outrancière, par le concept des "droits de l'homme", par l'individualisme (conduisant à l'extrême à des politiques gendéristes et favorable à la manie transgenre), par le matérialisme et par le progrès technique élevé à la plus haute valeur (via l'Intelligence Artificielle). L'objectif du libéralisme est d'abolir les États-nations et d'établir un gouvernement mondial basé sur les normes et règles occidentales.

C'est la ligne poursuivie par Biden et le parti démocrate moderne aux États-Unis et la plupart des dirigeants européens. Voilà ce qu'est le mondialisme. Il rejette catégoriquement l'Etat-Civilisation et toute velléité de multipolarité. C'est pourquoi l'Occident est prêt pour une guerre avec la Russie et la Chine. Dans un sens, cette guerre est déjà en cours - en Ukraine et dans le Pacifique (avec le problème de Taïwan), mais jusqu'à présent en s'appuyant sur des acteurs qui mènent leur combat par procuration.

Il existe une autre école influente en Occident - le réalisme dans les relations internationales. Ici, l'État-nation est considéré comme un élément nécessaire de l'ordre mondial, mais seuls ceux qui ont pu atteindre un haut niveau de développement économique, militaro-stratégique et technologique - presque toujours aux dépens des autres - possèdent la souveraineté. Alors que les libéraux voient l'avenir dans un gouvernement mondial, les réalistes voient une alliance de grandes puissances occidentales fixant des règles mondiales en leur faveur. Encore une fois - tant en théorie qu'en pratique, cet Occident rejette catégoriquement toute idée d'une civilisation d'État et d'un monde multipolaire.

Cela crée un conflit fondamental déjà au niveau théorique. Et le manque de compréhension mutuelle conduit ici aux conséquences les plus radicales au niveau de la confrontation directe.

Aux yeux des partisans de la multipolarité, l'Occident est aussi une civilisation-état, voire deux - celle de l'Amérique du Nord et celle de l'Europe. Mais les intellectuels occidentaux ne sont pas d'accord: ils n'ont pas de cadre théorique pour cela - ils connaissent soit le libéralisme soit le réalisme et non pas la multipolarité.

Cependant, il existe aussi des exceptions parmi les théoriciens occidentaux - comme Samuel Huntington ou Fabio Petito. Ils reconnaissent - contrairement à la grande majorité - la multipolarité et l'émergence de nouveaux acteurs sous la forme de civilisations. C'est réjouissant car de telles idées peuvent jeter un pont entre les partisans de la multipolarité (Russie, Chine, etc.) et l'Occident. Un tel pont rendrait au moins les négociations possibles. Tant que l'Occident rejettera catégoriquement la multipolarité et la notion même d'État-civilisation, le débat ne sera mené qu'au niveau de la force brute - de l'action militaire au blocus économique, en passant par les guerres d'information et par les sanctions, etc.

Pour gagner cette guerre et se défendre, la Russie elle-même doit d'abord comprendre clairement ce que signifie réellement la multipolarité. Nous nous battons déjà pour elle, et nous ne comprenons pas encore tout à fait ce qu'elle est. Il est urgent de dissoudre les think tanks libéraux créés pendant la période Gorbatchev-Eltsine et d'établir de nouveaux think tanks multipolaires. Le paradigme éducatif lui-même doit également être restructuré - en premier lieu au MGIMO, au MGU, au PFUR, à l'Institut Maurice Thorez, à l'Académie diplomatique et aux universités concernées. Enfin, nous devons vraiment nous tourner vers une école de pensée eurasienne à part entière, qui s'est avérée être d'une pertinence maximale, mais contre laquelle les atlantistes et les agents étrangers déclarés et dissimulés, qui ont pénétré profondément dans notre société, continuent de se battre.

20:16 Publié dans Définitions, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, alexandre douguine, multipolarité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 30 mai 2022

Civilisations et nations : l'ordre mondial multipolaire de Douguine

Civilisations et nations: l'ordre mondial multipolaire de Douguine

Par Valentina Schacht

Source: https://www.compact-online.de/zivilisationen-und-nationen-dugins-multipolare-weltordnung/?mc_cid=fbd916d5ee&mc_eid=128c71e308

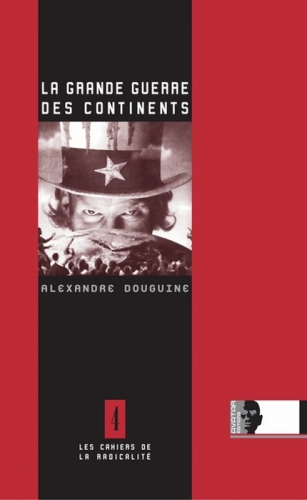

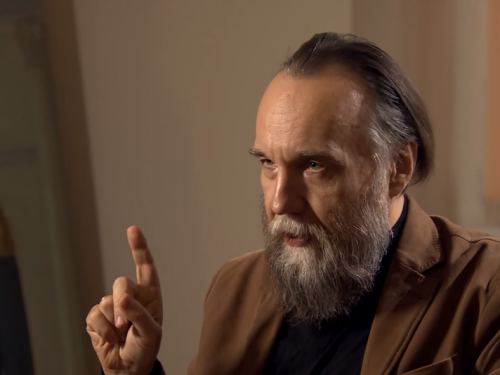

Le philosophe et expert en géopolitique russe Alexandre Douguine aspire à un ordre mondial entièrement nouveau. La guerre en Ukraine en est-elle le prélude ? Dans son dernier livre "Le grand réveil contre le grand reset", il a développé sa pensée de manière décisive.

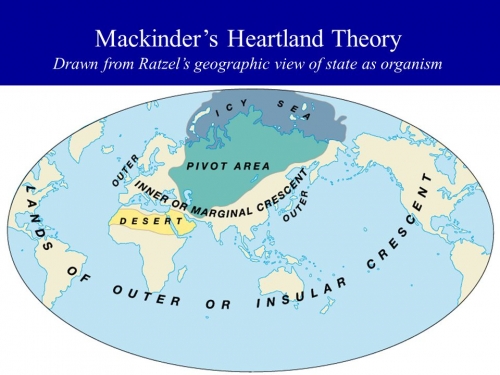

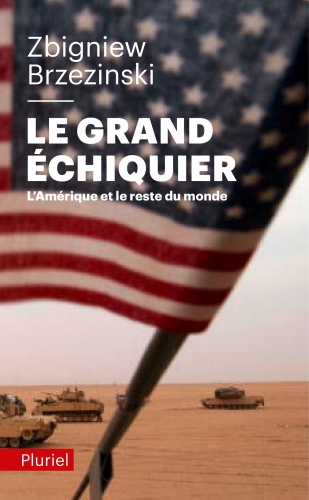

L'ouvrage d'Alexandre Douguine "Fondements de la géopolitique" (1997) est considéré comme une lecture standard dans les académies militaires russes. Le philosophe et politologue, qui a occupé la chaire de sociologie des relations internationales à l'université Lomonossov de Moscou, y divise la Terre en trois grandes régions principales du point de vue géopolitique: l'île mondiale (Etats-Unis et Grande-Bretagne), l'Eurasie (Europe centrale, Russie et Asie) et les terres marginales (les Etats situés entre les deux grandes régions citées précédemment).

Ses réflexions se fondent sur l'eurasisme, une école de pensée philosophique et géopolitique développée dans les années 1920 par des exilés russes autour de Nikolai Trubetzkoy et centrée sur l'idée d'une opposition fondamentale entre la puissance continentale russe et les puissances maritimes anglo-saxonnes.

Selon Douguine, qui a actualisé l'eurasisme, il existait et il existe toujours un conflit permanent entre les deux pôles d'un point de vue géostratégique, mais aussi idéologique: mondialisation et universalisme contre ordre mondial multipolaire et préservation des spécificités culturelles de chacun.

Abandon de l'État-nation ?

Au cœur de la critique de Douguine se trouve la prétention au leadership mondial du libéralisme (et du capitalisme) occidental, qu'il considère - sur ce point, il est d'accord avec son compagnon de route d'un temps, Alain de Benoist - comme la plus grande menace pour les peuples ou comme "l'ennemi principal".

Washington s'efforce d'imposer ce leadership soit par la séduction, soit par des méthodes subversives comme les "révolutions de couleur", soit carrément par la force militaire dans le monde entier. Ceux qui ne se soumettent pas volontairement au diktat du capital financier, à la doctrine du libre-échange ou à des idées telles que l'approche gendériste de l'égalité entre les hommes et les femmes, seront victimes de soulèvements populaires mis en scène et/ou de la guerre, affirme Douguine tout de go.

Comme alternative à la mondialisation, Douguine esquisse son "idée eurasienne" ethnopluraliste, qui ne se limite pas à l'espace russo-asiatique et qui s'inspire explicitement du concept de grand espace de Carl Schmitt. Il écrit à ce sujet :

"L'idée eurasienne réunit en elle toutes les approches critiques de la mondialisation. L'eurasisme rejette catégoriquement la vision occidentale du monde selon laquelle la planète est divisée en un centre (le monde anglo-saxon et l'Europe) et des périphéries éloignées (l'Amérique du Sud, l'Afrique, l'Asie). Au lieu de cela, l'idée eurasienne voit le monde comme un ensemble d'espaces de vie politiques, culturels et économiques totalement différents qui correspondent les uns aux autres".

Douguine considère que l'ordre international avec les États-nations comme acteurs politiques souverains, le "système de la paix de Westphalie", est obsolète. Dans les faits, le pouvoir réel serait déjà détenu depuis longtemps par de toutes autres structures - supranationales ou même économiques.

Estimant que cet ordre westphalien ne peut plus être réinstallé, il plaide pour un système de relations internationales avec des "civilisations" (terme qu'il reprend de Samuel Huntington, mais en le réinterprétant selon son point de vue) comme nouveaux acteurs.

Souvent taxé de "nationaliste grand-russe", Douguine s'est démarqué du nationalisme depuis des années :

"Je ne suis pas moi-même un nationaliste, mais un traditionaliste".

Il poursuit :

"Il y a une nécessité géopolitique pour une fédération ou une alliance européenne, quelle qu'en soit la forme, si le continent veut jouer un rôle à l'avenir".

Dans ses "Fondements de la géopolitique", il écrit même :

"Le monde multipolaire ne considère pas la souveraineté des États-nations existants comme une vache sacrée, car cette souveraineté repose sur une base purement juridique et n'est pas soutenue par un potentiel militaire et politique suffisamment fort".

Dans les circonstances actuelles, "seul un bloc ou une coalition d'États peut prétendre à une véritable souveraineté".

Ensemble plutôt que les uns contre les autres

Outre la "civilisation" occidentale (Amérique du Nord et Europe occidentale), Douguine en identifie six autres, à savoir la civilisation orthodoxe ou eurasienne (les États de l'ex-Union soviétique et certaines parties de l'Europe de l'Est et du Sud), la civilisation islamique (Afrique du Nord, Asie occidentale et centrale et certaines parties de la région Pacifique), la civilisation chinoise (Chine, Taïwan et les États de l'ASEAN), la civilisation indienne (Inde, Népal et Maurice), la civilisation latino-américaine (Amérique du Sud et centrale) et la civilisation japonaise (Japon).

Ce modèle ne tient pas compte de l'Afrique, que Douguine considère comme une "civilisation potentielle" qui a encore besoin de temps pour se développer pleinement et entrer sur la scène politique mondiale.

En ce qui concerne les "civilisations", les nouveaux "pôles du monde multipolaire", il affirme qu'elles doivent être souveraines et dotées d'un centre de pouvoir légal "d'un point de vue juridique formel". Et il écrit :

"La zone dans laquelle une civilisation exerce son pouvoir de domination et fixe les règles du jeu en vigueur doit être différenciée et tenir dûment compte de la composition ethnique et confessionnelle de sa population".

Outre les groupes confessionnels, les classes sociales devraient également être représentées de manière adéquate et "légalement représentées" dans la "civilisation" concernée. Son objectif est en fin de compte une coexistence et une cohabitation plutôt qu'une opposition entre les civilisations et également entre les groupes de population au sein d'une même civilisation.

En exclusivité chez COMPACT : dans son dernier ouvrage "Le grand réveil contre la grande réinitialisation", Alexander Douguine appelle les Européens à une résistance sans compromis contre les élites mondiales. Un appel à la lutte contre le mondialisme, le transhumanisme, les expériences génétiques et la transformation du monde selon les idées de Klaus Schwab et de son Forum économique mondial. Commander ici: https://www.compact-shop.de/shop/buecher/alexander-dugin-das-grosse-erwachen-gegen-den-great-reset/

20:08 Publié dans Actualité, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 20 mai 2022

Empire et praxis

Empire et praxis

par Aleksandr Dugin

Source: https://www.ideeazione.com/impero-e-prassi/

Quels sont les facteurs décisifs pour la restauration d'un véritable Empire en Russie ?

Cette question a été posée très sérieusement par le Père Vladimir Tsvetkov, prieur de l'Ermitage de Sofronie près d'Arzamas (ci-dessous), dans une formulation très profonde : pour quoi devons-nous prier ? En fait, la même question a été posée à Konstantin Malofeev lors de la présentation de son livre Empire : Où est l'Empire aujourd'hui ?

Je viens d'achever un nouveau livre, Genèse et Empire, une sorte d'"Encyclopédie de l'idée impériale", dans lequel j'expose le thème de l'ontologie impériale, de la figure archétypale du Roi de la Paix, des diverses formes de monarchie sacrée, en passant par une vue d'ensemble des empires historiques - y compris la mission de Katechon et la dialectique de la Russie impériale - et les simulacres d'"Empire", tels que l'Empire britannique et l'"Empire" américain moderne.

Il s'agit de thèmes et de théories profonds et fondamentaux, dont on ne peut toutefois pas tirer directement de conclusions pratiques. C'est pourquoi j'ai décidé de traiter la question du Père Vladimir de manière systématique et j'ai proposé une série de thèses. Il s'agit d'une ébauche, je serais reconnaissant pour tous ajouts et commentaires.

- L'empire peut être restauré en Russie à la suite d'un miracle divin. Tout empire a une origine surnaturelle. Si ce n'est pas un miracle de Dieu, alors c'est un "miracle noir" du diable. Les êtres humains ne sont pas capables de créer un empire. C'est toujours quelque chose de sacré. S'il n'y a pas de miracle, il n'y a pas d'empire, mais notre foi est dans le Dieu vivant, dans le Dieu qui fait des merveilles.

- L'Empire vit dans l'Église. L'enseignement religieux et eschatologique sur l'empire et la monarchie orthodoxe, ainsi que sur le rôle du tsar russe en tant que Katechon, a été développé en détail dans l'Église orthodoxe russe hors de Russie. La glorification des martyrs royaux et de tous les nouveaux martyrs de Russie fait partie de cet enseignement. Après la réunion du Patriarcat de Moscou et de l'Eglise orthodoxe russe hors de Russie dans les années 1990, cet enseignement a été généralement accepté par l'Eglise orthodoxe russe dans son ensemble, et aucune autre doctrine normative de la théologie politique de l'orthodoxie n'a été créée dans l'EOR elle-même pendant la période soviétique (et elle ne pouvait l'être après l'échec des rénovateurs). Par conséquent, la monarchie orthodoxe est le seul modèle normatif du christianisme orthodoxe russe. Les "libéraux d'église" bruyants et insistants ne comptent pas, ils ne sont que des "agents étrangers".

- L'empire (comme la monarchie) est une institution. La restauration de l'Empire peut se faire par une réforme politique à grande échelle, en révisant le cadre juridique russe dans l'esprit de l'autocratie. Le travail politico-philosophique et juridique est important ici.

- L'empire peut être fondé par une dynastie. Bien qu'aucune ligne de succession strictement directe du dernier empereur russe n'ait survécu, il y a les Romanov et, au 18e siècle, le trône russe a été occupé par des parents plus éloignés. C'est ici que la ligne Kirillovich, quelle que soit la façon dont elle est traitée en Russie aujourd'hui, a la plus solide base.

- Un empire peut être créé par de véritables succès militaires et l'expansion d'une zone de contrôle. Le pouvoir interne devient alors évident. L'agrégation même des terres russes - avec sa dépendance à la fois de la puissance militaire et de l'économie, de la diplomatie et de la culture - renforce le potentiel impérial.

- L'empire peut vivre selon la volonté du peuple. Dans ce cas, l'empire n'est pas établi du haut vers le bas, mais est exigé par le peuple, depuis la base vers le haut. C'est le scénario Zemsky. Le Zemsky sobor prend la décision historique que l'empire est et restaure la monarchie. Le culte moderne de Staline, répandu dans le peuple, d'un point de vue sociologique, n'est rien d'autre qu'une forme de "monarchisme par le bas", une demande de tsars.

- Un empire peut être déclaré par un dirigeant fort. Dans l'histoire romaine, le passage de la République à l'Empire s'est fait par la dictature de Jules César. Le nom "César" est ensuite devenu synonyme d'empereur, de roi. Bien qu'Auguste soit devenu empereur de plein droit, en réalité Jules César l'était déjà.

Il est difficile de dire à l'avance quel est le point principal. Actuellement, toutes ces conditions préalables sont présentes sous une forme ou une autre, mais aucune d'entre elles n'est encore clairement dominante. On peut supposer une combinaison de plusieurs points ou la sélection de certains au détriment d'autres ; on ne peut même pas exclure leur complète synergie. Si l'Empire est notre objectif (et s'il ne l'est pas, nous sommes perdus), nous savons maintenant ce pour quoi nous devons prier, ce pour quoi nous devons nous battre et ce que nous devons faire.

Le plus important est de ne jamais perdre de vue l'essentiel : l'Empire est un phénomène d'ordre spirituel, ce qui signifie que sans la volonté divine et sa providence, il ne sera qu'un simulacre. La chose principale dans l'Empire est un miracle. Ce n'est donc qu'au nom d'un miracle, dans l'attente d'un miracle, qu'il est possible de vivre. Sans lui, tout cela n'a pas de sens. Le miracle est le sens de notre vie. Un miracle impérial.

19 mai 2022

15:59 Publié dans Définitions, Nouvelle Droite | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : empire, définition, alexandre douguine, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, russie, impérialité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 04 mai 2022

Le Nouvel Ordre Mondial dans le contexte des théories des relations internationales

Le Nouvel Ordre Mondial dans le contexte des théories des relations internationales

Alexandre Douguine

Source: https://www.geopolitika.ru/en/article/nwo-context-international-relations-theories

Nous devons comprendre ce qui se passe pour nous et autour de nous. Pour ce faire, le bon sens ne suffit pas, il faut des méthodologies. Considérons donc l'OMS (Opération militaire spéciale) dans le contexte d'une discipline comme les relations internationales (RI).

Il existe deux grandes écoles de pensée en relations internationales: le réalisme et le libéralisme. Nous allons discuter de celles-ci, bien qu'il en existe d'autres, mais ces deux-là sont les principales. Si vous n'êtes pas familier avec ces théories, n'essayez pas de deviner ce que l'on entend ici par "réalisme" et "libéralisme", la signification des termes serait tirée du contexte.

Ainsi, le réalisme en RI repose sur la reconnaissance de la souveraineté absolue de l'État-nation; cela correspond au système westphalien de relations internationales qui a émergé en Europe à la suite de la guerre de 30 ans qui s'est terminée en 1648. Depuis lors, le principe de souveraineté est resté fondamental dans le système du droit international.

Les réalistes RI sont ceux qui tirent les conclusions les plus radicales du principe de souveraineté et pensent que les États-nations souverains existeront toujours. Cela se justifie par la compréhension que les réalistes ont de la nature humaine: ils sont convaincus que l'homme, dans son état naturel, est enclin au chaos et à la violence contre les plus faibles, et qu'un État est donc nécessaire pour empêcher cela; en outre, il ne devrait y avoir aucune autorité au-dessus de l'État pour limiter la souveraineté. Le paysage de la politique internationale consiste donc en un équilibre des forces en constante évolution entre les États souverains. Le fort attaque le faible, mais le faible peut toujours se tourner vers le fort pour obtenir de l'aide. Des coalitions, des pactes et des alliances se forment. Chaque État souverain défend ses intérêts nationaux sur la base d'un froid calcul rationnel.

Le principe de souveraineté rend les guerres entre États possibles (personne ne peut interdire à quelqu'un d'en haut de faire la guerre, car il n'y a rien de plus élevé qu'un État), mais en même temps la paix est également possible, si elle est avantageuse pour les États, ou si dans une guerre il n'y a pas d'issue univoque.

C'est ainsi que les réalistes voient le monde. En Occident, cette école a toujours été assez forte et a même prévalu, aux États-Unis, elle reste assez influente aujourd'hui: environ la moitié des politiciens américains et des experts en RI suivent cette approche, qui a dominé pendant la présidence Trump, la plupart des républicains (sauf les néocons) et certains démocrates y penchent.

Considérons maintenant le libéralisme en RI. Ici, le concept est très différent. L'histoire est vue comme un progrès social continu, l'État n'est qu'une étape sur la route du progrès, et tôt ou tard, il est appelé à disparaître. Puisque la souveraineté est entachée d'une possibilité de guerre, il faut essayer de la surmonter et de créer des structures supranationales qui la limitent d'abord, puis l'abolissent complètement.

Les libéraux de la RI sont convaincus qu'un gouvernement mondial doit être établi et que l'humanité doit être unie sous l'impulsion des forces les plus "progressistes", c'est-à-dire les libéraux eux-mêmes. Pour les libéraux de la RI, la nature humaine n'est pas une constante (comme c'est le cas pour les réalistes) mais peut et doit être changée. L'éducation, l'endoctrinement, les médias, la propagande des valeurs libérales et d'autres formes de contrôle des esprits sont utilisés à cette fin. L'humanité dans son ensemble doit devenir libérale et tout ce qui est illibéral doit être exterminé et banni. Car ce sont là les "ennemis de la société ouverte", les "illibéraux". Après la destruction des "illibéraux", il y aura une paix mondiale - et personne ne sera en guerre contre personne. Pour l'instant, la guerre est nécessaire, mais uniquement contre les "illibéraux" qui "entravent le progrès", défient le pouvoir des élites mondiales libérales et ne sont donc pas "humains", en aucune façon, et peuvent donc être traités de n'importe quelle manière - jusqu'à l'extermination totale (y compris l'utilisation de pandémies artificielles et d'armes biologiques).

Dans un avenir proche, selon ce concept, les États seront abolis et tous les humains se mélangeront, créant une société civile planétaire, un seul monde. C'est ce que l'on appelle le "globalisme". Le globalisme est la théorie et la pratique du libéralisme dans les RI.

La nouvelle version du libéralisme comporte un élément complémentaire aujourd'hui: l'intelligence artificielle dominera l'humanité, les gens deviendront d'abord sans sexe, puis "immortels", ils vivront dans le cyberespace et leur conscience et leur mémoire seront stockées sur des serveurs en nuage, les nouvelles générations seront créées dans une éprouvette ou imprimées par une imprimante 3D.

Tout cela se reflète dans le projet Great Reset du fondateur du Forum de Davos, Klaus Schwab.

Les libéraux constituent l'autre moitié des politiciens et des experts en relations internationales en Occident. Leur influence augmente progressivement et dépasse parfois celle des réalistes en matière de RI. L'actuelle administration Biden et la majorité du parti démocrate américain sont des libéraux qui poussent dans ce sens. Les libéraux sont également dominants dans l'UE, qui est la mise en œuvre d'un tel projet, puisqu'elle vise à construire une structure supranationale. Ce sont les libéraux en matière de RI qui ont conçu et créé la Société des Nations, puis l'ONU, le Tribunal de La Haye, la Cour européenne des droits de l'homme, ainsi que le FMI, la Banque mondiale, l'OMS, le système éducatif de Bologne, la numérisation et tous les projets et réseaux mondialistes, sont tous l'œuvre des libéraux. Les libéraux russes font partie intégrante de cette secte mondiale, qui a toutes les caractéristiques d'une secte totalitaire.

Appliquons maintenant ces définitions au NOM (Nouvel Ordre Mondial). Après l'effondrement de l'URSS, l'Ukraine est devenue un outil des libéraux et des réalistes au sein des RI - précisément un outil de l'Occident. Les libéraux du MdD ont encouragé l'intégration de l'Ukraine dans le monde global et ont soutenu ses aspirations à rejoindre l'Union européenne et l'OTAN (l'aile militaire du globalisme); les réalistes du MdD ont utilisé l'Ukraine dans leurs intérêts contre la Russie; pour ce faire, il était nécessaire de faire de l'Ukraine un État-nation, ce qui contredisait l'agenda purement libéral. C'est ainsi que s'est formée la synthèse du libéralisme ukrainien et du nazisme contre laquelle l'Opération Militaire Spéciale se bat. Le nazisme en acte en Ukraine (l'Extrême droite, le Bataillon Azov et d'autres structures interdites en Russie) était nécessaire pour construire une nation et un État souverain le plus rapidement possible. L'intégration dans l'Union européenne exigeait une image ludique et comiquement pacifiste (ce fut le choix de Zelenski). Le dénominateur commun était l'OTAN. C'est ainsi que les libéraux et les réalistes IR ont obtenu un consensus russophobe en Ukraine. Lorsque cela était nécessaire, ils ont fermé les yeux sur le nazisme, les valeurs libérales et les parades de la gay pride.

Venons-en maintenant à la Russie. En Russie, depuis le début des années 1990, sous Eltsine, Tchoubais et Gaidar, le libéralisme a fermement dominé les RI. La Russie d'alors, comme l'Ukraine d'aujourd'hui, rêvait de rejoindre l'Europe et d'adhérer à l'OTAN. Si cela avait exigé une plus grande désintégration, les libéraux du Kremlin auraient été prêts à le faire aussi; mais à un moment donné, Eltsine lui-même et son ministre des affaires étrangères Evgueni Primakov ont légèrement ajusté l'agenda: Eltsine n'appréciait pas le séparatisme en Tchétchénie, Primakov a déployé un avion au-dessus de l'Atlantique pendant le bombardement de la Yougoslavie par l'OTAN. Il s'agissait de faibles signes de réalisme. La souveraineté et les intérêts nationaux étaient invoqués, mais de manière hésitante, timide.

Le vrai réalisme a commencé lorsque Poutine est arrivé au pouvoir. Il a vu que ses prédécesseurs avaient affaibli la souveraineté à l'extrême, happés qu'ils étaient par la mondialisation, et que le pays était par conséquent sous contrôle étranger. Poutine a commencé à restaurer la souveraineté. Tout d'abord, dans la Fédération de Russie elle-même - la deuxième campagne de Tchétchénie, la suppression des clauses de souveraineté de la Constitution, etc., puis il a commencé à s'occuper de l'espace post-soviétique - ce furent les événements d'août 2008 dans le Caucase du Sud, puis la Crimée et le Donbass en 2014. Dans le même temps, il est révélateur que la communauté internationale des experts (SWOP, RIAC, etc.) et le MGIMO ont continué à être complètement dominés par la ligne du libéralisme. Le réalisme n'a jamais été mentionné. Les élites sont restées libérales - tant celles qui s'opposaient ouvertement à Poutine que celles qui acceptaient à contrecœur de se soumettre à lui.

L'Opération Militaire Spéciale a, comme un flash-back, éclairé la situation au sein du ministère russe de la Défense. Derrière l'Ukraine, il y a une alliance de libéraux et, en partie, de réalistes au sein du ministère de la Défense, c'est-à-dire les forces du mondialisme qui se sont retournées contre la Russie. Pour les libéraux (et Biden et son administration (Blinken and Co.), comme Clinton et Obama avant lui, appartiennent précisément à cette école), la Russie est l'ennemi absolu, car elle constitue un obstacle sérieux à la mondialisation, à l'instauration d'un gouvernement mondial et d'un monde unipolaire. Pour les réalistes américains (et en Europe les réalistes sont très faibles et à peine représentés) la Russie est un concurrent pour le contrôle de l'espace de la planète. Ils sont généralement hostiles, mais pour eux, soutenir l'Ukraine contre la Russie n'est pas une question de vie ou de mort: les intérêts fondamentaux des Etats-Unis ne sont pas affectés par ce conflit. Il est possible de trouver un terrain d'entente avec eux, pas avec les libéraux.

Pour les libéraux de la RI, cependant, c'est une question de principe. L'issue de l'Opération Militaire Spéciale déterminera s'il y aura ou non un gouvernement mondial. La victoire de la Russie signifierait la création d'un monde entièrement multipolaire dans lequel la Russie (et la Chine et, dans un avenir proche, l'Inde) jouirait d'une souveraineté réelle et forte, tandis que les positions des entités alliées de l'Occident libéral, qui acceptent la mondialisation et sont prêtes à compromettre leur souveraineté, seraient dramatiquement affaiblies.

En conclusion, le libéralisme dans les RI vise à imposer la politique du genre, la guerre de l'information et la guerre hybride, l'intelligence artificielle et le post-humanisme, mais le réalisme évolue également de son côté: confirmant la logique de S. Huntington (incidemment, un partisan du réalisme dans les RI), qui parlait du "choc des civilisations", les principaux acteurs ne sont pas des États mais des civilisations, ce qu'il appelle les Grands Espaces. Ainsi, le réalisme glisse progressivement vers la théorie du monde multipolaire, où les pôles ne sont plus les États-nations, mais les États-continents, les empires. Ceci est également clairement visible dans le déroulement de l'Opération Militaire Spéciale.

En termes de diverses théories des relations internationales, l'Opération lancée par la Russie en Ukraine a simultanément inauguré un conflit entre :

- l'unipolarité et la multipolarité,

- le réalisme et le libéralisme dans les RI,

- la petite identité (nazisme ukrainien artificiel) et la grande identité (fraternité eurasienne de la Russie),

- la civilisation de la terre (Land Power) contre la civilisation de la mer (Sea Power) dans la bataille pour la zone côtière (Rimland), qu'a toujours explicité la géopolitique,

- l'État défaillant et l'empire résurgent.

Sous nos yeux et avec nos mains et notre sang, maintenant - en ce moment même - la grande histoire des idées est en train de se faire.

19:18 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, alexandre douguine, relations internationales, école réaliste, réalisme ri |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 30 avril 2022

Les peuples d'Europe se soulèveront contre les élites mondialistes

Les peuples d'Europe se soulèveront contre les élites mondialistes

Entretien avec Alexandre Douguine pour Nexus

Propos recueillis par Lorenzo Maria Pacini

1) Alexander Goulievitch, le conflit actuel entre la Russie et l'Ukraine modifie l'ordre géopolitique mondial de manière multipolaire. À votre avis, à quoi ressemblera l'architecture internationale - disons, dans les cinq prochaines années - lorsque les combats seront terminés ? Qu'est-ce qui va changer exactement, quels équilibres de pouvoir sur l'échiquier mondial vont émerger et/ou être configurés ?

Tout d'abord, un système de trois pôles s'est clairement formé. Chacun d'entre eux a son propre domaine de responsabilité, sa propre monnaie de réserve, son propre ensemble de valeurs culturelles, sa propre stratégie indépendante.

Ce n'est pas une seule humanité normative qui émergera (en tant que projection de l'Occident libéral et de ses normes et règles), mais trois. Pas un seul ordre libéral basé sur les règles occidentales, mais trois ordres civilisationnels différents - avec des idéologies différentes. Ce sera un coup dur pour le mondialisme.

Suite à cet effondrement du monde global, d'autres civilisations se joindront à cette multipolarité. Tout d'abord, je pense, l'Inde. Elle a son propre système, une démographie énorme, un potentiel économique puissant. Le monde peut devenir quadripolaire assez rapidement. Puis viendra le temps du monde islamique, où l'Iran, le Pakistan, la Turquie, et aussi la Syrie, sont déjà des entités souveraines.

L'Amérique latine et l'Afrique graviteront dans le même sens.

Et parallèlement à cela, je pense qu'une guerre civile va commencer en Europe - les peuples d'Europe se soulèveront contre les élites mondialistes. Lorsque les continentalistes auront gagné, l'Europe se sera organisée en un autre pôle.

Et enfin, sous les coups de toutes parts, la dictature mondialiste aux États-Unis elle-même s'effondrera, et les Trumpistes comme les continentaux américains créeront un nouvel État. Peut-être le plus fort, peut-être pas.

2) La lutte géopolitique est aussi un "choc des civilisations", selon l'expression de Huntington, qui contraste avec la "fin de l'histoire" prônée par Fukuyama. Plusieurs fois dans vos discours, vous avez parlé d'une "guerre de l'esprit" quand vous évoquiez ce qui se passe. Pourriez-vous expliquer plus clairement votre vision métaphysique de ce conflit ?

C'est une longue histoire. Je suis un traditionaliste, et je crois que le monde moderne est l'opposé du monde de la Tradition. L'Occident moderne a détruit sa propre tradition, la tradition médiévale, la tradition antique, et détruit la tradition chez les autres peuples. En bref, l'Occident moderne est le Satan collectif, l'Antéchrist. À la fin des temps, et nous vivons à la fin des temps, Satan l'emporte sur ceux qui restent fidèles à Dieu, à l'ordre sacré. Mais cela ne dure pas longtemps. Dans la bataille finale, les armées de l'archange Michel, c'est-à-dire nous, sont victorieuses. C'est là l'essentiel : c'est le combat de la Tradition contre le monde moderne, le monde de la Révolution conservatrice. Pour les chrétiens, c'est une guerre contre l'Antéchrist, pour les musulmans contre Dajjal, pour les hindous contre le Kali Yuga, pour les Chinois contre le capitalisme et l'impérialisme occidentaux.

3) En Italie, vous avez été appelé à plusieurs reprises "l'idéologue de Poutine" et "le Raspoutine du Kremlin". Une grande partie de la presse italienne vous associe politiquement à l'extrême-droite, vous qualifiant de "fasciste" ou de "néo-nazi". Et cela - comme pour toute personne qui reçoit une "étiquette idéologique" de la part des médias - a en tout cas contribué à changer les perceptions des Italiens, intellectuels ou simples citoyens. À votre avis, qu'est-ce qui a suscité des étiquettes aussi peu judicieuses ?

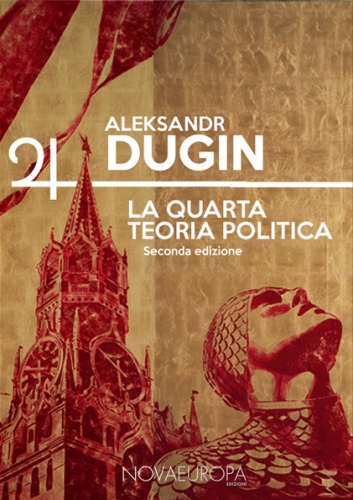

Je suis une personne assez courageuse, et si j'étais un fasciste ou un nazi, je le dirais. Et je me moque de ce que les autres en pensent. De même, si j'étais communiste. Mais je ne suis pas un nazi, un fasciste ou un communiste, et je détaille ma critique de ces visions du monde dans La quatrième théorie politique et dans mes autres écrits. Je suis contre l'Occident moderne et toutes ses idéologies - libéralisme, communisme et fascisme. Pour moi, les sujets normatifs de ces trois visions - l'individu, la classe et la nation (et encore moins la race) ne sont pas acceptables. Je crois que le sujet de la politique devrait être le Dasein ou le peuple compris existentiellement, non pas une nation politique, mais l'unité historique et culturelle d'un tout organique - toujours ouvert et sans rapport avec la citoyenneté ou l'ethnicité. Une nation est une unité de destin.

Mais le libéralisme qui prévaut aujourd'hui ne permet pas la possibilité même d'une critique à partir de la position de la Quatrième théorie politique. Tout ce qui s'y oppose doit être considéré soit comme du fascisme, soit comme du communisme. Les libéraux ne discutent donc pas avec moi, ils se contentent de me diaboliser, de me bannir, puis de colporter une caricature qu'ils ont eux-mêmes créée et qui n'a absolument rien à voir avec moi ou avec mes idées.

Il en va de même pour Poutine. Il n'est clairement pas un libéral, mais pas non plus un communiste et encore moins un nationaliste. Comment le définissez-vous en Occident? Comme un mélange de Staline et d'Hitler, il ne faut pas longtemps aux libéraux pour se décider. Et il n'est ni l'un ni l'autre. Les libéraux ne sont pas des nazis, mais ils se comportent comme des nazis. Et leur comportement rappelle également les procès staliniens, même s'ils ne sont pas communistes.

Je sais tout cela depuis ma jeunesse soviétique : le libéralisme est devenu si totalitaire qu'il ne tolère pas la dissidence et est incapable de polémiquer. Il s'agit d'un monologue. Un tel monologue narcissique sans cervelle est la chose la plus désagréable du fascisme et du communisme. C'est la méthode privilégiée du libéralisme aujourd'hui : si vous n'êtes pas un libéral, vous êtes un ennemi de la société ouverte, c'est-à-dire un "fasciste" Cela ne peut être modifié selon les vicissitudes du moment. Le camp de concentration idéologique en Occident et dans le monde disparaîtra en même temps que le libéralisme, tout comme les autres idéologies totalitaires occidentales ont disparu.

4) Dites-nous, s'il vous plaît, pour notre public italien, qui est de plus en plus intéressé par vos idées, mais qui, en même temps, n'écoute souvent que ce qui est diffusé par les grands médias : quelle est votre relation avec Vladimir Poutine ?

Poutine et moi sommes inspirés par la logique du destin russe, défendons l'identité russe, sommes dévoués à la civilisation russe et sommes conscients des règles du grand jeu géopolitique. Je pense que cette coïncidence est spontanée.

5) Votre quatrième théorie politique est un dépassement des trois grandes doctrines politiques, et elle fascine aussi les Européens, y compris les Italiens. Y a-t-il, en fait, un élément nouveau qui offre des possibilités pour l'avenir - y compris pour notre pays ? Et, à votre avis, quel rôle joue l'Italie dans la renaissance de l'Europe ? Et dans quelle mesure votre Quatrième théorie politique peut-elle être une voie à suivre ?

Je ne peux pas dire que je suis particulièrement impressionné par le patriotisme italien. Je ne suis pas non plus impressionné par aucun État-nation bourgeois créé à l'époque moderne. J'admire Rome et l'Empire romain. Je suis fasciné par la Renaissance italienne. J'aime beaucoup les régions italiennes - la Sicile, le Nord, etc. Et je suis très impressionné par les travaux et les idées du traditionaliste italien Julius Evola.

La quatrième théorie politique en Italie doit se fonder logiquement sur le Dasein italien. Mais qu'est-ce que c'est ? Chaque nation a son propre Dasein. Ce n'est pas une catégorie formelle - pas la citoyenneté, pas l'ethnicité, pas la langue... C'est la structure de la vie et la relation à la mort, c'est la profondeur d'une culture métaphysique et existentielle. Parfois, je pense que je ressens le Dasein italien et que je l'admire. Mais cela nécessite une sérieuse philosophie là. Dans ma série de livres, Noomachia, l'un des volumes est consacré au Logos latin. Je me penche sur l'histoire de l'Italie, de la Rome antique à nos jours. Mais il ne s'agit encore que d'une approche préliminaire. Décrire et explorer le Dasein italien est l'affaire des Italiens eux-mêmes. C'est également le point sur lequel doit être construite la version italienne spécifique de la Quatrième théorie politique. D'ailleurs, de telles études ont déjà été lancées en Espagne, au Brésil, en Argentine et dans d'autres pays.

6) En raison des sanctions (passées et présentes), la Russie est et sera contrainte d'accroître son indépendance vis-à-vis de la finance occidentale. Et selon certains, la possibilité d'un retour à l'étalon-or, surmontant la monnaie fiduciaire qui prévaut depuis les années 1970, lorsque les États-Unis ont imposé au monde une monnaie abstraite sans valeur, est proche. En outre, l'or a une signification symbolique précise que les traditions spirituelles ont toujours prise en compte. Pensez-vous qu'un tel scénario n'aurait qu'une signification économique, ou aurait-il également une signification plus large ?

Je m'en tiens ici plutôt à la théorie économique développée par Ezra Pound dans ses Cantos. L'étalon-or est une catégorie associée à quelque chose d'étranger à une économie particulière et porte déjà en elle, bien que modifiée, la référence à la caisse d'émission. Une monnaie nationale ne devrait être liée qu'au volume du produit national. L'émission est l'affaire de la banque centrale souveraine sans aucune référence à une quelconque mesure étrangère, qu'il s'agisse d'une monnaie de réserve mondiale ou d'un étalon-or. Et pour éviter de déclencher l'inflation, les investissements stratégiques doivent être acheminés par une deuxième boucle, distincte de celle du consommateur de masse. Ce modèle ne dépend pas de l'idéologie - le New Deal de Roosevelt, l'économie de Staline de 1928-1953 et l'économie de HJalmar Schacht ont été toutes aussi efficaces, tandis que le libéralisme, le communisme ou le nazisme dans d'autres versions auraient pu se conjuguer avec stagnation, effondrement et dégradation. La souveraineté économique, que Pound vantait et que le brillant Silvio Gesell a tenté d'incarner, est la solution optimale.

21:00 Publié dans Actualité, Entretiens, Eurasisme | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : alexandre douguine, entretien, nouvelle droite, nouvelle droite russe, actualité, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 24 avril 2022

Maurizio Murelli, éditeur de Douguine : "Voilà ce qui se cache derrière le conflit en Ukraine"

Maurizio Murelli, éditeur de Douguine : "Voilà ce qui se cache derrière le conflit en Ukraine"

Propos recueillis par Umberto Baccolo

Maurizio Murelli est un homme qui a le courage de ses idées, aussi impopulaires soient-elles et quel que soit le prix à payer, et depuis les années 1980, il mène une bataille culturelle et politique pour les diffuser. Anti-libéral, anti-américain, il est issu de la droite radicale, un milieu dans lequel il jouit encore d'un grand crédit, mais qu'il a depuis longtemps abandonné pour d'autres rivages : en particulier, la Quatrième théorie politique d'Alexandre Douguine, le philosophe et politologue russe que Murelli invite à parler en Italie depuis le début des années 1990 et qu'il traduit et publie ici. Il l'a d'abord fait avec sa propre Società Editrice Barbarossa et le magazine associé Orion, et maintenant avec AGA Editrice, qui a pris leur place.

Murelli, comme Douguine, est l'un des rares intellectuels qui, dans ce conflit en Ukraine, se range ouvertement du côté des Russes, sans demi-mesure ni circonlocutions verbales. Dans cette longue interview, il explique en détail pourquoi, racontant ce qu'il n'a pas eu le temps d'expliquer complètement lorsqu'il était récemment invité à la télévision en prime time sur Rete4. Si, après avoir lu l'interview, vous êtes curieux de connaître sa figure atypique, je vous renvoie au film documentaire "Maurizio Murelli - Non siamo caduti d'autunno", que j'ai réalisé en 2020 et qui peut être visionné gratuitement sur YouTube, une chaîne où il a enregistré un certain nombre de visites.

Dans votre analyse très suivie sur Facebook, vous expliquez que la vraie guerre n'est pas celle de l'Ukraine, car elle n'est qu'un front dans un affrontement plus vaste. Pouvez-vous expliquer ce que vous entendez par là et quels sont les véritables éléments en jeu ?

L'Ukraine est un champ de bataille de la Grande Guerre mondiale à laquelle les États-Unis ont donné un nouvel élan et une accélération dans les années 1990 afin d'imposer leur ordre mondial au monde, se concevant, depuis leur naissance, comme la véritable Jérusalem terrestre, leur peuple comme le véritable "peuple élu" dont la mission messianique est de racheter toute l'humanité. Cette vision qui est la leur est bien expliquée par John Kleeves dans le livre "A Dangerous Country" qu'en tant qu'éditeur j'ai publié pour la première fois en 1998 et ai réédité chez AGA Editrice en 2017. Pour être plus précis, la Grande Guerre mondiale pour la conquête du monde a commencé bien avant les années 1990, lorsque - faisant passer la doctrine Monroe d'une échelle continentale à une échelle mondiale - ils sont intervenus en Europe pendant la Première Guerre mondiale, ce qui a permis aux États-Unis d'être décisifs dans la rédaction du traité de Versailles avec lequel ils ont élaboré une première ébauche du nouvel ordre mondial redessinant, de mèche avec les Britanniques, la géographie de l'Europe et aussi de l'Afrique. Ils ont franchi une nouvelle étape avec la Seconde Guerre mondiale, dans laquelle ils sont intervenus via le Pacifique. À cette époque, leur principal intérêt était d'établir leur propre domination dans la zone Pacifique en désintégrant le Japon. La dynamique liée au jeu des alliances a amené les États-Unis sur le théâtre de guerre européen qu'ils ont colonisé à la fin de la guerre. Et voici le Pacte deYalta, qui constitue pour les États-Unis une sorte d'"image fixe" dans leur progression vers l'établissement de leur propre domination mondiale. Les États-Unis se sont retrouvés libérés du pacte de Yalta à la fin des années 1980 avec l'implosion de l'URSS et après avoir réduit le Panama, qui voulait nationaliser le canal, à une peau de chagrin en arrêtant et traînant le président Noriega enchaîné dans sa propre prison ; ils ont commencé leurs guerres au Moyen-Orient, d'abord en parrainant la guerre contre l'Iran, puis en intervenant directement en Irak, puis en Syrie, en Somalie, en Libye et même en Europe contre la Serbie. Tous ces États étaient, avant les années 1990, alliés ou sous le parapluie protecteur de l'URSS. Ils ont promu la guerre de vingt ans contre l'Afghanistan tandis que, par diverses flatteries, ils ont incorporé dans l'OTAN - la feuille de vigne de l'armée américaine - plus ou moins tous les pays de l'ancien Pacte de Varsovie. L'Ukraine est restée à l'extérieur. Par le biais de diverses "révolutions colorées", ils ont tenté de miner de l'intérieur tous les autres États qui n'avaient pas encore été subjugués, jusqu'au coup d'État de Maidan en Ukraine. Il faudrait être myope ou de mauvaise foi, mais il faudrait aussi être un idiot cognitif, pour ne pas voir le schéma global de cette guerre mondiale, asymétrique et menée aussi avec des armes commerciales et des sanctions, souvent contre les Etats les plus faibles, comme ceux d'Afrique, où les Américains se présentent avec le Colt et le chéquier, pour les soumettre, d'une manière ou d'une autre, à leur propre domination. C'est dans ce cadre, certainement décliné en complot par les pontes, que je soutiens que l'Ukraine n'est qu'un des nombreux champs de bataille de la grande guerre biséculaire.

Vous avez longtemps pris vos distances avec la zone dite de la droite radicale, mais il est intéressant de noter que, tout comme dans la gauche radicale, cette situation a produit la plus violente fracture interne depuis longtemps. À votre avis, quelle en est la raison, car cette même crise russo-ukrainienne a créé des divisions aussi nettes et féroces entre les héritiers des idéologies du 20e siècle ?

Tant la "droite radicale" que la "gauche radicale" ne sont que les déchets des orthodoxies idéologiques de la première moitié du 20e siècle, des résidus humains qui vivent depuis des décennies sur des malentendus et des illusions. Tant la "droite" que la "gauche" ne sont pas les antagonistes du libéralisme, mais en sont l'expression directe. Ils sont progressivement conquis et enivrés par les valeurs libérales et à la fin, rayés de la carte, ils rivalisent entre eux pour être plus libéraux que les libéraux déclarés. La gauche vit un véritable psychodrame. La Russie, berceau du communisme inversé, a brisé la propre certitude centrée sur l'inéluctabilité du cours historique tel que conçu par la gauche. Dans leur album de famille, il y a l'oncle Lénine qui est renié et reste seul comme une momie emblématique sur la Place Rouge. Pour eux, il était inéluctable que le Quatrième État, celui du prolétariat, batte le Troisième État, celui de la bourgeoisie et du capitalisme. C'est le contraire qui s'est produit. Pour l'essentiel, l'aile gauche a d'abord répudié le communisme, puis a recherché de nouvelles échelles de valeurs progressistes, toutes raffinées et essentiellement individualistes. Au point que si vous mettez une centaine de gauchistes devant vous, il n'y en a pas deux qui puissent se superposer, c'est-à-dire qu'ils auraient la même idée de comment être de gauche. Et en fait, ils sont tous en conflit les uns avec les autres pour revendiquer l'authentique "forme de la gauche". Mais je dois m'arrêter ici, car toute la question serait trop longue à expliquer. Les événements en cours en Ukraine obligent la "droite" et la "gauche" à prendre parti, tout en restant discrets sur la question. Et si la "droite" et donc les divers néo-fascismes s'enlisent sur un terrain romantique en étant fascinés par les runes et les croix gammées dextrogyres, la gauche, et même ceux qui se sont déclarés communistes, deviennent des serviteurs objectifs de l'impérialisme atlantiste qu'ils ne reconnaissent pas comme tel, tandis qu'en définissant la Fédération de Russie comme un empire, ils ne l'acceptent pas comme tel. Il y a aussi une sorte de ressentiment irrépressible envers la Russie pour la façon dont elle est passée du communisme à autre chose. Et ils sont fascinés par l'idée de résistance et autres bêtises du genre. Je salue avec un énorme plaisir cette désintégration idéologique de la droite et de la gauche, du communisme et du fascisme. Le champ des malentendus est en train d'être nettoyé. Je suis heureux de les voir se tenir côte à côte sur le même front pour défendre les valeurs libérales, l'atlantisme et l'impérialisme atlantique. En restant sur cette position, ils débarrassent le champ des cadavres idéologiques en faveur de ceux qui se sont depuis longtemps libérés des malentendus, en faveur de ceux qui adoptent aujourd'hui une véritable position révolutionnaire et donc une fonction antilibérale.

Pour en revenir à la question précédente, j'ai l'impression que beaucoup de gens, à commencer par Poutine lui-même et même Douguine qui parle de nazis et de dénazification, ont tendance à vouloir adapter cette situation à un affrontement entre les anciennes idéologies, où l'on ne sait plus très bien qui sont les nazis et qui sont les communistes. Je pense que cette façon de voir les choses est vieille et inefficace, cependant, que ce qui est en jeu n'est pas le fascisme et le communisme, qu'en pensez-vous ?

Tout d'abord, il faut partir du fait que les terminologies, et donc les langues, utilisées en Occident et celles utilisées en Orient, ce qui vaut également pour la Chine, l'Inde, etc., ne sont pas superposables car elles sont différentes. Pour les détenteurs du pouvoir, les terminologies doivent agir sur ce qu'on appelle l'imaginaire collectif, et les imaginaires en Orient sont différents de ceux qui circulent en Occident. Dans l'imaginaire collectif russe, le nazisme est l'idéologie qui a tenté d'anéantir l'identité russe et qui a fait 26 millions de victimes russes. La Seconde Guerre mondiale se décline en guerre patriotique, c'est-à-dire en guerre pour la défense de l'identité russe que les nazis voulaient nier. Ainsi, en se mettant au service de l'atlantisme, les Ukrainiens ont en fait sublimé les nazis en niant l'identité russe. Il faut garder à l'esprit que non seulement il y a eu huit ans de guerre dans le Donbass pour éradiquer les russophones et les russophiles, mais que durant ces mêmes huit années, il y a eu une répression meurtrière à l'intérieur de l'Ukraine, qui a pris la forme d'une persécution de la culture russe, d'une interdiction de l'utilisation de la langue russe, de la mise hors la loi des partis russophones et d'une série d'assassinats ciblés, de persécutions physiques et d'emprisonnements, des faits dont personne ne parle mais qui sont pourtant bien documentés. Poutine voit dans tout cela une action nazie. Personnellement, je pense que l'adoption par Poutine du concept de "dénazification" a également une valeur tactique: il voulait anticiper l'utilisation de l'épithète "nazi" à son encontre, car c'est ce que fait l'Occident lorsqu'il veut objectiver comme un mal absolu ceux qui sont ses ennemis; il l'a également fait avec Saddam, Assad, Milosevic, etc. Quant à Douguine, il sait très bien que le nazisme en circulation aujourd'hui n'a rien à voir avec le nazisme historique (quoi qu'on pense du nazisme) et l'identifie comme un néo-produit du libéralisme, un faux nazisme créé en "laboratoire" par ceux qui n'ont aucun problème à l'exploiter de diverses manières, selon leur convenance, en la désignant comme un danger dans certains contextes, à d'autres moments, dans d'autres contextes - comme dans le cas de l'Ukraine ou, pour ne citer qu'un exemple, comme au Chili dans les années 1970 - comme quelque chose de bénéfique. Selon Aleksandr Douguine, donc, le nazisme, le fascisme et le communisme étaient une réponse au libéralisme tout au long de la Modernité. Sa position nous place au-delà de la post-modernité (celle dans laquelle nous vivons aujourd'hui) et de la modernité, celle dans laquelle nous vivons hier, et se situe précisément dans la pré-modernité, c'est-à-dire dans le monde de la Tradition. Par conséquent, en ce sens, il est anti-nazi. Il faut également admettre que la remise en jeu du nazisme par Poutine est l'une des causes du court-circuit déterminé dans la "droite" et la "gauche" et que, par conséquent, dans la perspective de leur désintégration, il s'agissait d'une remise en jeu efficace et bénéfique".

D'autre part, en parlant du monde de l'information, vous dénoncez - en apportant beaucoup de vidéos et de témoignages et de preuves à l'appui - que les médias sont très partiaux et ne font que de la propagande, nous abreuvant de beaucoup de mensonges, afin de pousser les gens à accepter les conséquences économiques d'une crise avec les Russes, en les mettant en exergue et en exaltant les Ukrainiens. Cependant, une chose doit être dite: dans nos talk-shows et nos journaux, une large place est accordée à ceux qui théorisent que les Ukrainiens doivent se rendre, que nous ne devons pas intervenir, et que Poutine a ses nombreuses bonnes raisons: outre les divers Orsini et Canfora, intellectuels de gauche respectés, et l'ANPI de Pagliarulo, nous avons même trouvé beaucoup de place pour Douguine et aussi pour vous, des figures souvent diabolisées... Comment voyez-vous cela ? S'agit-il d'une question de respect du pluralisme ou d'autre chose ?

Il y a un cas d'école que personne ne mentionne. En 1990, une femme s'est présentée au Congrès américain en tant qu'infirmière réfugiée du Koweït, racontant des horreurs indicibles commises par les troupes irakiennes, telles que des enfants jetés sur des baïonnettes, des viols et des massacres généralisés, un récit qui a été immédiatement soutenu même par Amnesty International, ainsi que par tous les médias occidentaux. Le témoignage de l'infirmière autoproclamée a déclenché l'indignation qui a conduit à l'opération "Tempête du désert", la première guerre du Golfe en Irak.

Cependant, le témoignage de l'infirmière Nayirah était un mensonge colossal, à commencer par le nom avec lequel elle s'est présentée. Son vrai nom était, en fait, Saud al Sabath, et elle n'était ni une réfugiée ni une infirmière pauvre, mais la très riche fille de l'ambassadeur du Koweït aux États-Unis. Il a fallu attendre 1992 pour découvrir la vérité révélée par le New York Times, qui a également documenté la façon dont le canular a été conçu par une agence de publicité, Hill & Knowlton (le lavage de conscience médiatique posthume typique: jamais la dénonciation du bobard n'a lieu alors que le mensonge est flagrant). Ce faux témoignage repris sans critique par les médias occidentaux a servi à galvaniser et à pousser les masses à donner leur consentement à la guerre d'invasion de l'Irak. Une "petite guerre" qui a coûté la vie à 100.000 Irakiens, dont 2300 civils. Plus célèbre est le canular utilisé comme casus belli pour la deuxième guerre du Golfe, l'exposition par Colin Powell à l'ONU de la fameuse fiole qui, selon le général qui s'était recyclé dans la politique, contenait suffisamment d'anthrax pour exterminer la population d'une grande ville. Cet autre canular, qui, comme le premier, a galvanisé les Occidentaux, a coûté une "petite guerre" qui a duré huit ans et fait 63.000 victimes civiles plus environ 8.000 militaires. C'est plus ou moins le même schéma qui est utilisé en Ukraine, avec une méthode beaucoup plus harcelante, la quasi-totalité des soi-disant correspondants de guerre se faisant passer pour des témoins oculaires et se laissant mener par les milices ukrainiennes qui leur montrent ce qu'ils veulent voir et leur disent ce qui leur convient le mieux. Si l'un de ces correspondants essayait de dire aux Ukrainiens quelque chose qu'ils n'aiment pas, nous verrions combien de minutes il lui faudrait pour recevoir un ordre de quitter le territoire. Il y a trois ou quatre correspondants de guerre occidentaux sur le front russe. Il faut aller sur les télévisions russes, chinoises, arabes, indiennes et africaines, ainsi que sur les chaînes Telegram pour voir une réalité totalement différente. J'ai archivé une centaine de films du front russe, réalisés par des journalistes indépendants, dont aucun ne sera jamais diffusé à la télévision grand public. "Une large place est accordée dans les talk-shows à ceux qui avancent des points de vue opposés à ceux des pro-Ukraine" dites-vous ? Je suis plus ou moins tous ces talk-shows où ceux qui s'expriment contre le récit atlantiste sont mis devant une sorte de peloton d'exécution; des duels à un contre dix, où l'animateur interrompt avec ses remarques souvent déplacées afin de frustrer le récit du dissident, puis, fatalement, diffuse les publicités quand il a l'intention de faire taire le récit qui est désagréable pour lui. Au fait, si, au moment de la soi-disant urgence sanitaire pandémique, quiconque passait à la télévision et s'écartait du récit de Speranza & C. devait faire précéder sa déclaration de: "Je suis vacciné et sur-vacciné mais, en ce qui concerne.... Je ne suis pas d'accord", ici chacun doit d'abord faire profession d'amour inconditionnel pour l'atlantisme, dire que la Russie est un envahisseur et l'Ukraine une victime, que Poutine est un monstre, etc. Bien sûr, ils doivent soutenir qu'en Italie il y a une information pluraliste et pour cette raison ils donnent un peu d'espace à ceux qui ont des positions légèrement différentes. Sauf à les massacrer et à les obliger à s'exprimer entre un film horrible et larmoyant et un autre. Chaque jour, je reçois des demandes pour passer à la télévision ou pour favoriser la présence de Douguine. Je n'ai accepté qu'une seule fois, et Aleksandr Douguine que je protège, en dictant les conditions de l'émission. Quand ils n'acceptent pas et sont intelligents, malgré les supplications, Douguine ne passe pas à la télévision. Laissez-les faire leur propre petit théâtre.

Enfin, vous êtes doué pour faire des prédictions. Selon vous, quelles seront les conséquences à court, moyen et long terme de ce conflit pour l'Italie ? Et comment pensez-vous que le conflit va se poursuivre ?